A Missing Story

As urban transportation bicycling becomes more popular, planners and advocates often use “bike friendly cities” like Portland, Amsterdam and Copenhagen as examples for facilities as well as political strategies and tactics. Although these are wonderful cities with dazzling bike networks and impressive ridership numbers, a narrative is emerging that bicycle advocacy needs to follow their methods. On the contrary, the bicycle movement in Los Angeles is not rooted in mimcry of Europe or the “whitest city in America”. It owes much of its progress to the participation of immigrants of color who can share uncountable stories of everyday bicycling in their countries of origin.

The stories often sound like this one (told to author Allison Mannos as a family story):

In the 1950’s, my mother grew up in a rural area of Toisan, in southern China. When she was two, she contracted polio in her leg. At that time, polio vaccines weren’t available in her area and other developing places. Without medicine, doctors said her leg would require amputation. Her grandfather, in an attempt to provide whatever he could, hopped on his bicycle and pedaled down unpaved dirt roads to numerous villages nearby, looking for the prescribed milk and herbal remedies, which were scarce. He eventually found enough milk and herbs, and he ferried them back to my mother with his bicycle, which helped to save her leg.

Although it’s tempting to focus on the role of bicycle as savior, the moral of the story is actually the ubiquity of bicycling—the foregone conclusion of it. These journeys for milk and medicine were simply one of many daily trips made for commuting, errands, and everyday life. This unconscious, mainstream, and frequent use of the bicycle to accomplish daily tasks without a dedicated bicycling infrastructure is common to developing places around the world.

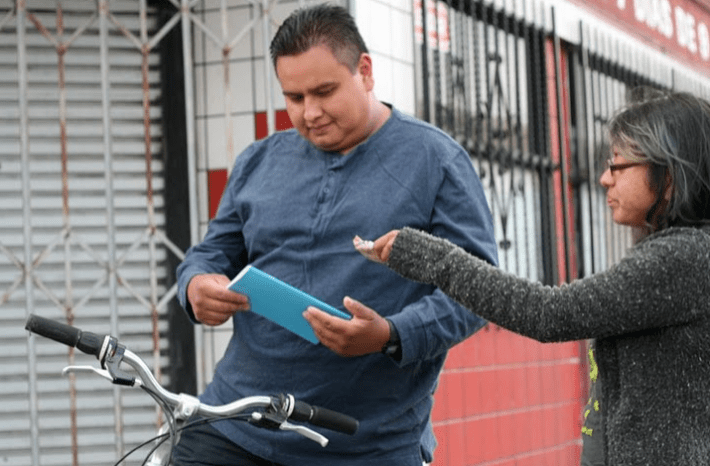

Although not all Los Angeles’ bicyclists are immigrants from these places, work within the bicycling community reveals that the success of Los Angeles bicycling is based on the established behavioral patterns of these people. They are immigrants, or children of immigrants, from rural and urban parts of Asia, Latin America, and Africa; their motivation to ride does not necessarily stem from an environmental or political stance. For them, bicycling is a cultural norm of inexpensive transportation that provides means for survival.

Moving Forward, Margin to Center

Infamous for car culture and congestion, Los Angeles has dramatically developed a large and visible bicycling community in the last ten years. It boasts hundreds of monthly rides, over half a dozen bicycle repair community spaces, an outspoken advocacy community, and a recent ambitious update to its bicycle master plan. While some planners and advocates attribute these changes to Los Angeles adopting ideas from bike-friendlier cities, the characterization overlooks the fact that a substantial number of people already rode in relative invisibility—invisibility based on their race, immigration, or low-income status. Many of these riders live and/or work in neglected parts of Los Angeles including portions of Westlake/MacArthur Park, Downtown, South LA, Pacoima/Van Nuys, and East LA.

Reframing the discussion to reorient around this segment of bicyclists is paramount for planners and advocates to ground bicycling progress within social justice. The scope of change dramatically spans theoretical and practical. At a conceptual level, current planning methodologies are flawed. Within advocacy, efforts to get new, more affluent, and choice riders (read: converting drivers), to commute by bicycle are misplaced.

Problems in Planning Practice

An example of problematic planning practice can be found in the use of “Best Practice” reports, often used to guide infrastructure, program and policy recommendations. While the identification of a “best” is convenient, closer examination reveals that most of the examples are from European and American cities, perpetuating institutionalized Eurocentricity and American exceptionalism. In fact, numerous lessons can be learned from other places with high non-motorized mode use as well. A study by Michael Replogle revealed that “non-motorized vehicle trips account for 25-80 percent of trips in many Asian cities, more than anywhere else in the world.” Recently, the Institute for Transportation Development Policy awarded Guangzhou, China the 2011 Sustainable Transport Award for its Bus Rapid Transit accompanied with its bike parking and bike share programs. Though Guangzhou’s land use and density are arguably more similar to Los Angeles than Portland or Amsterdam or Copenhagen, Chinese solutions rarely make it into Best Practice documents.

Evidence of a successful solution from cities not usually identified as exemplary can be witnessed in the wildly successful practice of temporary car-free street closures for the benefits of bicyclists and pedestrians. Since these have become extremely popular in American cities, it is only Los Angeles’ incarnation that cites the practice’s origin from Bogotá, Colombia by dubbing it “CicLAvia”.

Advocacy Blinders and Invisibility

In terms of advocacy, outreach efforts should expand ideas of target communities, not only to fill the ranks with as many bicycling voices as possible, but also to create a comprehensively transformative movement. Frequently, for example, discussions of the inequity in bicycling between men and women tend to focus on educated, middle-class white women (especially mothers), and usually do not examine the barriers to bicycling for, say, women of color. This narrow approach in advocacy and planning often misses solutions to engage and serve the existing, dedicated population of low-income cyclists of color; in fact, it instead ignores them or takes their lifestyles for granted.

What has made it possible for some bicyclists to remain invisible? These communities of color and/or immigrant communities, though more culturally accustomed to bicycling, may struggle with establishing a political voice, especially within bicycling advocacy. Language, but also cultural representation is an obvious culprit. The Long Beach Blue Line Bike/Ped Access Plan comprehensively conducted multilingual outreach in English, Spanish, and Khmer, to accommodate neighborhoods in the scope area. But, for a vastly scattered bicycling community in a multi-centric city, does multilingual outreach alone ensure diverse participation?

Legal/voting status may also inhibit some immigrants from participating in the planning process making it less likely that elected officials are concerned about their needs. A larger gap is that the planning and advocacy communities need to directly educate and engage these communities to be able to prioritize and advocate for bike infrastructure in their neighborhoods. Lastly, these communities need to be explictly sought out and courted for their input and knowledge.

Solutions Moving Forward

Recent updates in the Los Angeles Bicycle Plan contained provisions that prioritize the needs of these long-overlooked neighborhoods and riders. New policies weight bicycle infrastructure priority heavily in low-income areas, which means they will receive facilities sooner. This goal was originally not on the radar for the City or outspoken advocates. The shift was largely based on input from members of the LACBC City of Lights program, which targets low-income Latino immigrants with bilingual saftey, repair, and outreach programming.

Through focus on these cyclists and neighborhoods, which were historically neglected, the City can support healthy, sustainable lifestyles and reduce the high vehicle-collision rates in the most heavily-trafficked, industrial areas. This contrasts with the previous strategy of prioritizing improvements for streets in affluent areas, trying to persuade residents who prefer driving to give bicycling a try. Moving forward, City of Lights will work in conjunction with key community organizations and social service providers, to coordinate massive bilingual outreach along the low-income corridors to be created by the updated bike plan.

These are the types of strategies that need to be adopted by the broader advocacy and planning community in order to build bicycle infrastructure that serves current and future bike commuters most effectively. More importantly, focusing on bicycling in neglected, low-income, and immigrant communities of color will help us build the broader movement many of us desire: one that combines the concerns of advocates for low-income families, immigrant rights, social justice, and bicycling to harness the ability of bicycling to transcend ethnicity, class, gender, immigration status, or other hierarchies.