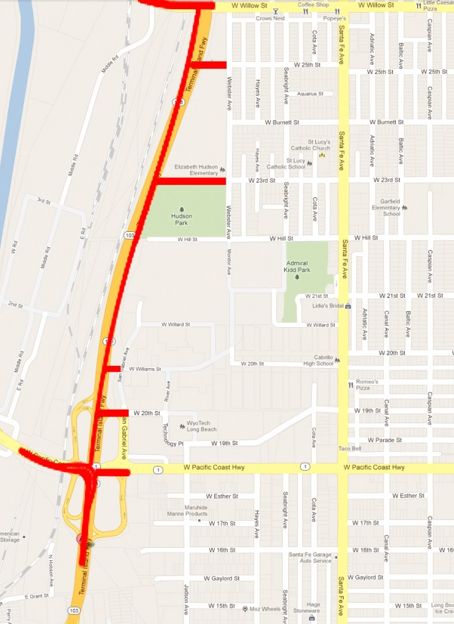

Last night, the Long Beach City Council voted unanimously to (once again) approved a motion to pursue a grant in order to further a study on the removal of the northern portion of the Terminal Island Freeway (I-103) that sits above Pacific Coast Highway in West Long Beach.

This marks the second bold decision by the council--following last year's vote to seek a CalTrans grant that was ultimately not achieved--to push forward on what could mark one of the largest freeway removals in Southern California history, stretching from slightly south of PCH all the way to Willow Street.

The Terminal Island Freeway has been at the center of a proposed restructuring since 2010, when community leaders pointed out a simple thing: the existing northern length of the freeway, following the development of the 20-mile long Alameda Corridor and the still-underway modernization of the Intermodal Container Transfer Facility (ICTF) by Union Pacific Railroad, is redundant.

Not only do shipping companies use it less and less, the traffic itself matches those of 4th Street along Retro Row (some 13,700 AADT). And if plans for ICTF follow through, you can drop that down to 8,700 AADT--less than the traffic 3rd Street receives in the quiet neighborhood of Alamitos Beach.

Detractors of redundant freeway stretch removals in general have, also in general, the evidence stacked against them. Freeway removals from Portland, Oregon (Harbor Drive Freeway) to Boston (Central Artery), from Seoul, Korea (Cheonggye Expressway) to Toronto (Gardiner Expressway) have proven multiple things that are commonly not considered or otherwise misinterpreted. Benefits of freeway removal include:

- The traffic congestion feared by having a lesser roadway capacity can be absorbed by alternate routes (regard San Francisco's Central Freeway removal discussed below as well);

- Fewer people use their cars when roadway capacity is lessened1

- The removal of certain spans of roads does not mandate nor necessarily guarantee a needed shift in the entirety of transit paths (regard the removal of San Francisco's Embarcadero Freeway);

- And the excessive right-of-way paths can be altered into public, open space that generate activity on multiple levels--communal, civic, commercial--rather than simply diminish transit2

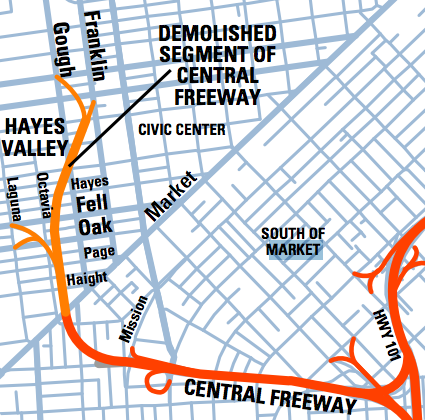

Take in depth one of the most known freeway removals in California, the Central Freeway that connected the 101 near downtown San Francisco to northern and western neighborhoods. The demolished segment of the freeway--the entire portion of it north of Market Street that extended into Hayes Valley--was part of a transit way that at its peak carried some 100,000 AADT.

That's a lotta cars.

Following the damage to the Central Freeway due to the 1989 Loma Prieta Earthquake as well as a partial closure in 1996, people began to reconsider retrofitting the extension. During the 1996 closure, the expected traffic congestion ultimately never appeared and a 1999 ballot initiative was approved to remove the freeway.

Officially closed in 2003 with the new-and-improved Octavia Boulevard opening in 2005, the boulevard's northern end not only rejuvenated the entirety of Hayes Valley's commercial and residential development, but also dropped traffic rates by over half since automobiles automatically diverted themselves to alternate routes.

With regard to Terminal Island, there is just as much possibility. Given that the state transfered ownership of this northern one-mile portion to Long Beach, the city has the jurisdiction over its fate--and if it can muster up the financial strength to continue forward (i.e. fund an EIR), the new space can open up some 25-acres of land that could be used to create one Long Beach's largest parks.

Perhaps this year will be more promising than last.

FOOTNOTES:

1. Evidence of this is shown in places such as the removal of I-264 in Virginia in 1996 (decrease of 14%); Bay Street in Toronto in 1990 (decrease of 21%); Ormeau Road in Belfast in 1994 (decrease of 18%); Europa Bridge in Zurich in 1991-92 (decrease in 5%). For more information, re: Cairns, S., Hass-Klau, C., and Goodwin, PB (1998). Traffic Impact of Highway Capacity Reductions: Assessment of the Evidence. Landor Publishing, London.

2. Examples include not just the Central Freeway removal discussed in the article but the Embarcadero Freeway removal which in turn created a "complete street" with serving multiple modes of exploration (walking, biking, driving, public transit) with enhances civic and commercial activity; the removal of the Harbor Drive Freeway in Portland, OR to create the 37-acre Tom McCall Waterfront Park; the removal of the Cheonggye Expressway in South Korea that ended in a 3.6 mile park; the reconfiguration of the Riverfront Parkway in Chattanooga, TN opened up access to the river as well as safer pedestrian access; and the removal of the Park East Freeway in Milwaukee that opened up massive redevelopment and reinvestment into the area.