"If you don't shut it down, we're going to shut you down!" shouted a woman dressed in hazmat gear (above, with skull on her back).

She had just angrily paraded in front of the Department of Toxic Substances Control (DTSC) officials, representatives of the Department of Public Health (DPH), and the moderator with her daughter, proclaiming that children should not have to wear protective gear to play outside.

One of the women standing with her moved towards a DTSC official waving a lemon from her yard and telling him to go ahead and make lemonade out of it.

The nun sitting near me appeared to say a silent Hail Mary and make the sign of the cross.

A young woman watching me scribble all this down furiously asked if I was press. She worked for Exide, she said.

"I bet you're popular tonight," I said.

The meeting at Resurrection Church in Boyle Heights to update the community on embattled Vernon battery recycler Exide's lead and arsenic emissions was packed to the brim with residents of Boyle Heights, Maywood, Vernon, Lynwood, and surrounding areas. All of whom wanted answers about the lead found at all of the 39 homes where soil was tested at depths of between zero and six inches for contaminants, and none of whom were happy.

The confirmation that the homes and schools tested both north and south of the Exide facility had levels of lead in the soil that exceeded 80 parts per million -- levels high enough to trigger further testing -- while daunting, was probably not surprising to most.

As Roberto Cabrales, an organizer with Communities for a Better Environment, proclaimed, "We're not here because we heard the information in the newspaper recently or last week. We're here because we've been hearing this stuff for the last 10 years, or even more...That this company is continuously...contaminating our communities."

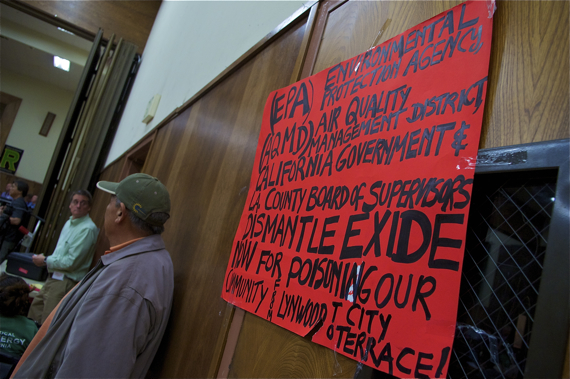

Many also saw the failure of the DTSC, the AQMD, or other authorities to hold Exide fully accountable for its violations, revoke its temporary permit, or have implemented long-term solutions by now as a deeply offensive lack of commitment to the well-being of residents.

Their anger boiled over when representatives of the DTSC and DPH suggested that, until more testing could be done and short-term solutions could be put in place, residents should always wash their hands and feet, put doormats in front of and just inside the entrances to their homes, thoroughly wash home-grown produce, and limit children's ability to play in the dirt.

"I'm a teacher, I'm pregnant, I own property here... I'm worried," said one woman. "Telling me I can get a doormat is...really ridiculous."

Another community organizer asked how washing home-grown produce would help mitigate contamination in vegetables that absorbed lead from the soil.

"We have residents who are growing food in their backyard and that's how they are feeding their families," he complained.

Covering up the contaminated soil with gravel or grass -- the short-term solutions the DTSC had suggested -- wouldn't change that or magically excise lead from their tomatoes.

"What does clean-up look like [to you]?" he asked, wanting to know when they might see long-term solutions.

Reiterating that the lead levels were not at an emergency hazard level, officials answered that by this Friday, Exide would be submitting plans to the DTSC detailing how they will conduct additional sampling and address conditions at the homes where lead concentrations had exceeded acceptable levels. Once the second round of sampling was complete, DTSC would have a better understanding of how deep the contamination ran and how broadly it extended and be able to formulate appropriate next steps then.

Those answers and the vague timelines offered for when contaminated soil might be removed from their properties -- should that happen at all -- were not enough to pacify residents.

Nor was Exide's claim that the idea that "Exide is contaminating the surrounding residential areas with lead" fell squarely into the category of "myth," as a myths vs. facts handout I received boldly suggested.

While many speakers last night acknowledged their communities were repositories for pollutants from a variety of sources, they were quick to point to the number of violations Exide has racked up over the years, its ongoing struggle to curb excessive lead emissions, and its reluctance to upgrade its equipment to comply with a new AQMD rule limiting arsenic emissions. They were not interested in hearing Exide's suggestion that the lead might have come from "freeway exhaust, other local industrial sources, and paint from or on older houses" or that residents shouldn't be too alarmed because "all but three soil samples at depth were below state public health hazard levels."

"I would like to acknowledge that the level of respect in this room has been absolutely appalling," began a staff attorney with CBE, "This is not the first time we've been here...And, so [for you] to come in here and to try to explain that the solution and the level of contamination that this community is suffering from is to wash hands or feet and wash vegetables is incredibly disrespectful. I hope that in the next meeting... you will come in here with something better to say than that."

As the evening wore on, officials continued to try to reassure residents that they were doing all they could to move the soil testing process along and encouraged them to take advantage of the free blood tests screening for lead exposure that the DPH would be offering (but paid for by Exide) between April 7th and September 14th. While it is now too late for health claims to be included in any settlement from Exide's bankruptcy proceedings, they felt it was important for people -- especially children -- to be tested.

Acknowledging the tests only would pinpoint recent, not chronic, lead exposure, a DPH official said they were still worthwhile. If a patient was found to have been exposed to lead, further testing for chronic exposure or other issues could take place at that time and treatment begun.

While residents appreciated that help, they clearly remained fearful.

The confirmation that there was contamination in their neighborhoods and at their schools meant, to them, that they had no safe haven.

"We appreciate you being here," CBE's Cabrales told officials, "but we will be here as long as we have to be. You want to go home...? We want to go home, too. Unfortunately our homes are contaminated because of all this junk."