Riding my bike the 15 miles between my apartment and a Move L.A. forum on the future of transit at Southwest College on a dreary Saturday morning while battling the tail end of a stubborn respiratory infection was not among the brightest ideas I had ever had, I reflected as it began to drizzle and my hacking started getting the best of me.

But I hadn't wanted to take the bus (buses, as, technically, I would have had to have taken two). Between the walking and the waiting for lines that run less frequently early on Saturday mornings, my door-to-door journey would probably come out at about two hours -- half the time it took me to ride the route.

And the scenes I passed at bus stops on my way down the length of Vermont were not exactly selling bus riding to me.

The many, many folks crowding narrow sidewalks at unprotected bus stops looked rather miserable in the areas where rain was falling. Most yanked hats down over their ears, snuggled deeper into jackets, held newspapers or other random things over their heads to fend off the drizzle, and huddled over their kids to keep them dry. There are actual bus "shelters," but they are few and far between, generally filthy and overflowing with trash, and offer little protection from the elements.

I even found myself dodging wet, frustrated people who had stepped out into the street to make the long-distance squint up Vermont that only regular bus riders can, searching in vain for a flash of orange. Others called out to ask if I had happened to pass a bus on its way to pick them up.

The state of the bus system in L.A. is not spectacular, in other words, despite the fact that it is responsible for ferrying 3/4 of all Metro transit riders (approximately 30 million people) back and forth per month.

But discussion of the bus situation was notably absent from the discussion on the future of transportation that unfolded over nearly five hours the morning of January 8.

Aside from the remarks of Southwest College alum Leticia Conley, who complained that some students' ability to access education could be harmed by having to rely on buses that only ran once an hour, most of the discussion focused on rail.

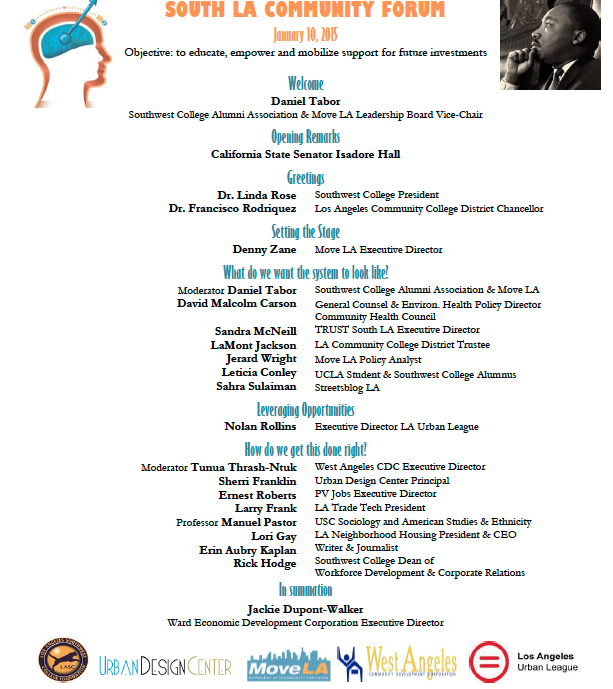

In some ways, the oversight was by design. Besides gathering together leaders from the African-American community to talk about opportunities to make investments in transit translate into investments in the development of South L.A., the larger goal of the forum was to build support for putting a proposal for "Measure R2" on the 2016 ballot.

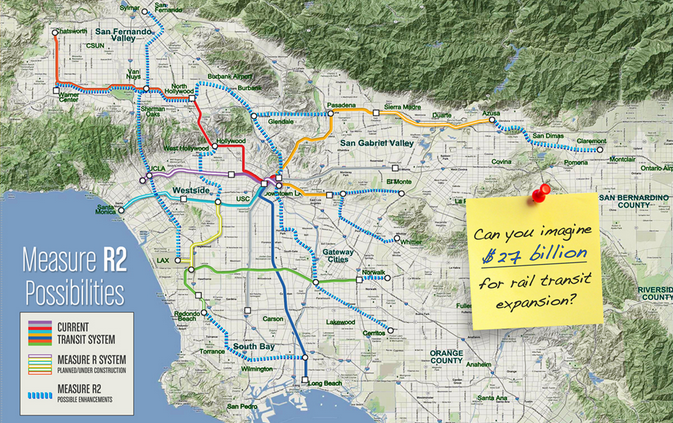

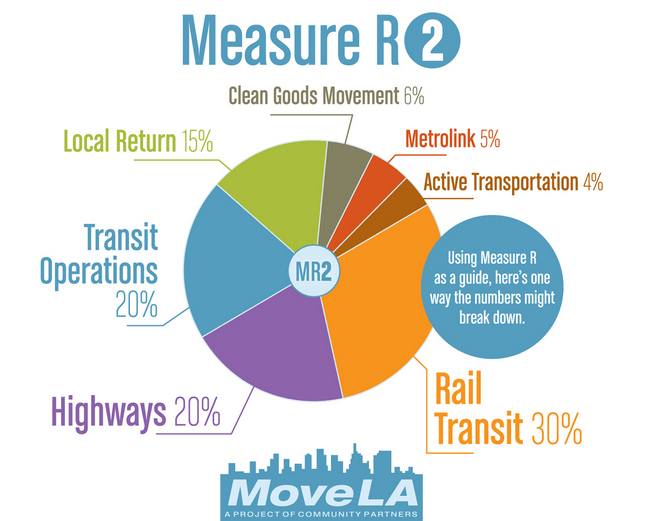

The "45-year county-wide half-cent sales tax, with project[ed] revenues [of] approximately $90 billion...would run concurrently with Measure R for R’s remaining 20+ years" and dedicate nearly a third of the funds toward rail (see map above; see Joe Linton's assessment of the proposed plan here).

A portion of the 5% ($4.5 billion) of the funds dedicated to what Move L.A. labels as "Grand Boulevards" could go to investing in better bus infrastructure along Rapid transit lines and bus-only lanes, "where appropriate," but other potential improvements to the bus network are not spelled out so clearly.

The other obvious reason the discussion focused on rail is because of the potential for neighborhood transformation that the dollars and infrastructure new rail lines bring can have in an economically challenged area like South L.A.

The emphasis being on "potential," of course.

As Erin Aubry Kaplan summarized succinctly in her assessment of the forum for KCET, "the Blue Line hasn't turned the poorest part of South L.A. into Beverly Hills" and "the link between transit and major community development [in] needy places...has yet to be fully exploited" in ways that benefit those residents.

But that potential for transformation is there, if harnessed properly, argued speakers that included Metro Board members Jackie Dupont-Walker and County Supervisor Mark Ridley-Thomas. As is the potential for turnover and displacement, if it is not.

Most of the businesses along the Gold Line through Boyle Heights, for example, neither benefited from the substantial mitigation funds set aside to assist them during construction of the line nor reaped any real bump in revenues from its arrival five years ago. Now, pending changes (like the development of Mariachi Plaza) and the trickling in of developers, speculators, and new, well-to-do homeowners have enticed some retail property owners along the corridor to begin seeking sizable raises in rents from their tenants.

Similarly, the expansion of USC and the arrival of the Expo Line in South L.A. fueled rampant real estate speculation well before construction of the line was complete. In the case of the Rolland Curtis Apartments (near the station at Vermont Ave.), wealthy developer Jeff Greene sent his low-income tenants illegal 60-day notices to vacate the property and allowed the building to fall into disrepair to encourage them to leave sooner. If TRUST South L.A. and Abode Communities hadn't stepped in to help tenants assert their rights and, ultimately, buy the building to safeguard it for affordable housing, the remaining tenants would have been displaced long ago (see more on that case, here).

Considering the level of need, asking non-profits to buy up TOD sites along burgeoning transit corridors is likely neither viable nor sustainable as a long-term development solution. And even affordable housing projects can fall far short of being truly affordable for those in most desperate need of them. Overlooking opportunities to leverage transportation funds to boost economic development from within the community can be similarly counterproductive, facilitating gentrification and sowing further distrust between city agencies and lower-income communities.

Harmonizing transit and community development, in short, will only come with better policy and planning intentionally aimed at doing so.

But that, according to many of the panelists, is more complicated than it might sound. It requires a great deal of investment in preparing communities to be able to take advantage of opportunities well ahead of ground being broken on projects. Their suggestions included: strengthening programs at community colleges and universities that prepare students from disadvantaged communities for careers at Metro or in planning; building the capacity of local entrepreneurs and contractors so they are prepared to work with Metro or are able to apply for mitigation funds during construction periods; investing in re-entry programs and follow-up efforts to ensure they and other disadvantaged workers keep jobs over the long-term; working with researchers to bring key lessons to bear in planning for development from within; leveraging the impact of future transportation funds by partnering with transit-oriented efforts aimed at boosting economic revitalization (e.g. the SLATE-Z proposal); using zoning, etc., to ensure developers will include affordable housing in TOD; creating TOD neighborhoods not just corridors; and actively engaging communities as partners in the long-term planning process from the outset.

Despite gains in some areas (like building relationships with community colleges), Metro continues to struggle in others. Most notably, according to both Ridley-Thomas and Dupont-Walker, in helping small and disadvantaged businesses participate in the opportunities provided by the "mega projects," despite it being a project requirement (see video of some of their comments here).

And where all these supplementary components might fit into the plans for Measure R2 is unclear. As Kaplan, Investing in Place advocate Jessica Meaney, and others wondered after the forum, do we have a good accounting of the extent to which Measure R's transportation dollars have been successful in addressing some of these bigger-picture transportation and development goals just yet? Should we have one before making decisions about how any dollars should be allocated, were voters to view a sales tax as viable way forward? Should we be thinking harder about the far-less-sexy-but-perhaps-more-important bones of the bus network and seeking innovative opportunities for enhancement and development there? At the very least to better complement opportunities created by rail?

I certainly don't have the answers.

A refreshingly frank Dupont-Walker acknowledged that Metro didn't have all the answers, either, and that Metro needed to hear from those dependent on transit (often those most absent from discussions about its future) and those whose communities will impacted by new infrastructure.

"Take a look at what we're calling our Transit-Oriented Development policy at Metro and give us good feedback on it," she said, reiterating her call for active and vigilant community participation in Metro's planning processes. "It was introduced...September of last year as a draft, and as we roll it out and attempt to implement it, it needs to be real and meet the needs of every sector, every subregion. And [South L.A.] should not be left out." (See policy motion here.)

"We won't be left out if you own something," Ridley-Thomas quipped. "I'm just saying..."

* * * *

*please note: Measure R2 information is currently missing from Move L.A.'s website. We'll post the appropriate links as soon as they become available.

What say you about the idea of a Measure R2 proposal? If in favor of it, what's on your wishlist? How should funds be allocated? Let us know below. Or attend Move L.A.'s next community forum on the topic, which will be held in the Valley on Feb. 26 (get details here).