While some might not relish the opportunity to stand out on a street corner and count passersby for two hours, I can honestly say I really enjoy the experience.

Not the act of counting of people, per se. But the chance to absorb the rhythm of a street. I actually spend a good deal of time moving along both Central Ave. (in South L.A.) and Soto St. (in Boyle Heights), where I am participating in the biennial Bike and Pedestrian Count this year. But standing in one place for two hours allows you to get a sense of how and why they are using the street -- indicators that can sometimes be just as important as quantitative data in regard to policy-making.

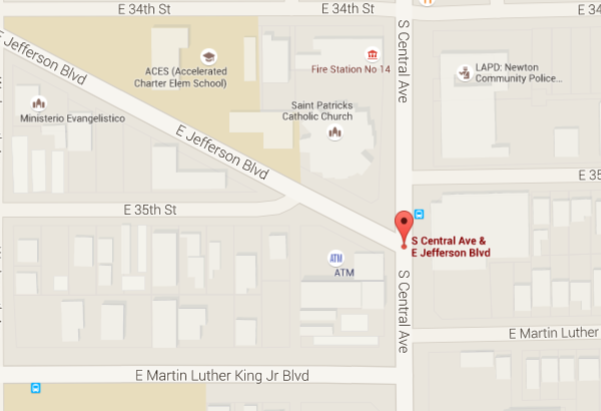

Perhaps most striking to me during my count shift on the west side of Central Ave. (between Jefferson and Martin Luther King, Jr. Blvd.) Wednesday was that, of the approximately 200 people that passed by me on foot or on bikes, only one elderly couple seemed to be out for a stroll. The rest appeared to be commuting, heading home from school, or running errands (many of those counted passed by a second time, often carrying something purchased at a nearby market).

That stands in stark contrast to more well-to-do neighborhoods where you are liable to see joggers at various times of the day or people taking in the sights, window shopping, walking a dog, or lingering over coffee and people watching.

When one of the students from nearby Jefferson High School (getting experience with data-gathering as part of a National Health Foundation program) was asked if she had ever walked the two blocks north to visit the 3 Worlds Cafe -- a project launched by chef Roy Choi that got its start at her high school -- she replied, "No, it's not safe."

To her and other residents I've spoken with, that section of Central doesn't feel very secure.

Pinning down exactly what makes a section of a street insecure can be tough, given that that sort of information tends to travel by word-of-mouth among residents and doesn't necessarily correlate with actual crime stats. When gang-bangers are enforcing territorial boundaries by intimidating local youth, for example, they do so knowing that those youth will not report them. So despite Compstat data showing the area around 3 Worlds Cafe as seeing less reported crime than, say, 41st St. (regularly used by students to move between Jefferson HS and Central Ave.), and despite the Newton Division of the LAPD being located practically next door to the cafe, youth are still reluctant to wander up that way.

Walkability for this community, in other words, hinges on much more than just traffic control.

But traffic is indeed a problem, too.

Central narrows as it heads southward from downtown, meaning the few cyclists that braved riding on the road often ended up in the gutter by the time they reached King Blvd., pictured above.

The corridor also becomes a bit of a bottleneck at the intersections of King Blvd. and Jefferson Ave., pictured below, where the heavily-trafficked streets all feed heavily into each other.

Because of all the right and left turns made on to and off Central, pedestrians and cyclists can only cross each of the intersections at two points instead of three. It can therefore take someone on foot several minutes to be able to move through and across the intersections. And they often have to do so while dodging right-turning drivers from Jefferson eager to avoid sitting through a long red light at King Blvd.

For pedestrians and cyclists accustomed to dodging traffic, the scenario this juncture presents is annoying, time-consuming, occasionally stressful, and sometimes frightening (especially at dusk and at night). But it is generally manageable and somehow sees fewer reported collisions between pedestrians/cyclists and cars than some of the intersections to the south.

For me, the issue of greatest concern was that so many of the people moving along the street tended to be unaccompanied kids.

Very young kids.

I counted 17 children under 10 years of age, two-thirds of whom were walking alone or with a young friend, and approximately 20 students of middle-school age. I spotted many others across the street. [The east sidewalk, tallied by my count partners, seemed even busier, given that staying on that side of the street allowed people to avoid getting stuck at the convergence of King Blvd. and Jefferson.]

Most appeared to be heading home from school or after-school programs, running errands, or heading for markets or McDonald's to grab dinner. All seemed to be incredibly well-versed in navigating major intersections. But with the days getting shorter and school now in session (two elementary schools are within a block of the intersections), I can only imagine how much more at-risk the tinier kids will be when visibility is tougher.

Working-class Latino and African-American cyclists of all ages were also out in abundance.

I counted approximately 70 on just the west side of the street during the two-hour period. Some were clearly commuters and appeared to be making their way deeper into South L.A. But the great majority seemed to be local. Some were students still wearing their uniforms. Some were men making market runs, including one who managed to balance 3 cases of water bottles between his chest and the handlebars as he pedaled. Other cyclists had more precious cargo, including a mother balancing her toddler on the center bar of her bike and a man that had modified the back wheel of his bike to give his son a place to stand (top photo) so that he could get both the boy and his daughter (on her own bike) home together.

All but a handful of the cyclists stuck to the sidewalk. The sidewalk both afforded them a buffer from the crush of traffic and allowed them to complete their errands without having to take a chance on crossing Central (in order to ride with traffic in the street).

The lack of access cyclists had to their own street was probably one of the more disheartening things I observed. Especially because it was clear that the vast majority were riding out of necessity -- the bicycle was their primary means of transportation.

Having to take refuge on the sidewalk made their trips all the more cumbersome. And it meant that they were forced to compete for space with the kids and families that comprised the bulk of the pedestrians.

Somehow they all made make it work -- I saw no collisions, even though the sidewalks got crowded at times. But it reminded me of the words of Adé Neff, founder of Leimert Park's Ride On! bike co-op, who once declared, “Too often in our community we adjust. We adjust to lack. We don’t complain — we just adjust.”

The ability of folks in lower-income communities of color to adjust to a lack of infrastructure is what has made it possible for them to survive and even thrive, despite the decades of disinvestment and disenfranchisement they have experienced.

But the certainty that those on the margins could "adjust to lack" seems to have emboldened Councilmember Curren Price to seek the removal of the (forthcoming) Central Ave. bike lane from the city's recently-approved Mobility Plan. And, perhaps most depressingly, it has allowed the Mayor's Office itself to sanction Price's efforts to thwart mobility via Great Streets' plans to pilot a road diet sans bike lane on Central, wholly undermining the mayor's own soaring rhetoric surrounding Great Streets, the Mobility Plan, and Vision Zero.

Recalling the city's bizarre justification for the move -- a standard bike lane wouldn't do enough to attract new cyclists between ages 8 and 80 -- as I stood counting cyclists on what is already the most heavily bike-trafficked street in all of South L.A., I found myself feeling a bit like the anti-Oprah.

You don't get a lane! You don't get a lane! And you don't get a lane!

But this time around, cyclists may be unwilling to adjust to being denied infrastructure. Local cyclists and residents in partnership with local health and mobility advocates from TRUST South L.A., Community Health Councils, and the Ride On! bike co-op plan to speak up at a safety pit stop and press event next Wednesday, September 23, at 6 p.m. on the corner of Central and Vernon. They are eager to have their voices heard, to have a dialogue with the councilmember and the mayor's office, they say, and to share how harrowing it can be to get to work, school, or market when they have to make those trips on a bike.

Whatever the outcome, it is clear that Central is ripe for some adjustment. Calming traffic and accommodating both pedestrians and cyclists are key to making the street safer. But as mobility patterns observed on the street suggest, those fixes won't be enough on their own. Investments in the surrounding community -- particularly in the youth and in addressing the push factors that send them into gangs -- are also of the essence. A safe space must also be a secure space if everyone is to be able to access it and enjoy it.

What was your experience doing bike/ped counts? What were your observations about how people were using their street? Let us know below.