As part of our End-of-the-Year Fundraising Drive, Streetsblog L.A. likes to look back at some of our most influential stories of the year. If you support our work, please consider making a donation today. Get started by clicking here. - DN

We were there, back in 2015, when then-Mayor Eric Garcetti dragged a desk out into the middle of a Boyle Heights street to announce Los Angeles’ Vision Zero Initiative – the effort to eliminate traffic deaths by the year 2025.

In the ensuing decade, traffic-related deaths have continued to rise, topping 300 in 2022 and 2023, and nearing 300 again this year. Despite being a lead implementing agency of Vision Zero, LAPD has both managed to contribute to that death toll and sought to shield themselves from accountability for it.

So this year, we took a look a number of the deaths they were ultimately responsible for.

The killing of 26-year-old pedestrian Luis Espinoza by an officer who had improperly deployed her emergency lights in order to speed across Southeast L.A. should have been an easy case for the department to publicly address. But, as we were able to show in our investigation, LAPD’s critical incident briefing omitted important information about how the crash unfolded while engaging in classic victim-blaming by emphasizing that Espinoza had been crossing against the light.

Although the officer traveled well over a mile along Century Boulevard, the video LAPD released included just 17 seconds of dash cam footage and cut out very early on in her trajectory. It did not specify her speed, how far she traveled against oncoming traffic, how many red lights she ran, or whether her sirens were deployed the whole time. Even the way the officer’s help calls were played over the security cam footage – suggesting she immediately called for help and rendered aid – appeared to deliberately misrepresent that timeline. Our review of the footage suggested the officer did not make the call for help until 23 seconds after LAPD implied she had and that she did not begin chest compressions on Espinoza – who came to rest over 100 feet from where he had initially been hit – until a minute and a half after striking him.

At the time, then-Chief Michel Moore indicated the case would be presented to the District Attorney "for filing considerations” when the investigation was complete. But a year later, charges have yet to be filed, the officer has yet to be named, and a full accounting of the officer’s actions has yet to be provided.

That kind of obfuscation makes naming and addressing dangerous behavior more difficult. Especially when it comes pursuits – one of the deadliest activities officers undertake.

This year, we tracked two pursuits – one official and one unofficial – that killed a total of three people. What we found was damning.

LAPD says department policy prioritizes the “balance test” – a weighing of the seriousness of the violations against the potential risks to officers or the public – to determine whether a pursuit should be initiated, continued, and/or abandoned. To that end, LAPD says, officers are trained to constantly monitor their surroundings – weather, roadway, neighborhood, and traffic conditions, the presence of pedestrians and cyclists, the relative speed of the pursuit, etc. – and factor it into their decision making. They are also reminded to ask themselves key questions – “Do we have a license plate?” “Do we have a known suspect?” and “Can we catch this person at another time?" – to help reduce pursuit footprints in communities.

Our close examination of a brief but harrowing pursuit that ended violently this past April showed policy and practice can diverge significantly. After rewinding the dashcam audio multiple times, we were able to determine that the driver of the patrol vehicle was a training officer – the very person tasked with teaching and reinforcing the balance test in new recruits. But instead of guiding the probie he was paired with through the balance test, we found he had been laser focused on radio protocol and suspect apprehension.

Had he helped the probie perform the balance test, they would have concluded the pursuit should never have been undertaken. The driver was trackable via an electronic device he had allegedly stolen, the crime he had committed was relatively minor, and they had his license plate. But the training officer never once questioned the need for the pursuit or assessed the threat to public safety. Instead, mid-pursuit, he was heard telling the probie to get confirmation that a crime had been committed.

And as they turned onto Hooper – a relatively narrow semi-residential street that sees pretty heavy northbound traffic in the mornings – the training officer escalated the pursuit by requesting more backup. The end result was utter devastation: the fleeing driver mowed down 46-year-old José David Monsalve Rojas (who was crossing Hooper with his bike), pinballed his way between parked, northbound vehicles, and a telephone pole, and flipped his own vehicle. Monsalve Rojas died instantly. The driver, 23-year-old Germaine Smith, died a few days later.

Rather than express concern about how the pursuit had unfolded or answer Streetsblog’s questions about the training officer, LAPD worked to depict Smith as a prolific thief as a way to justify the carnage. And because the evaluations of individual pursuits tend not to be made public, it is unknown how the department handled such an egregious flouting of policy and public safety.

The department was similarly evasive when officers involved in an unofficial pursuit in Hollywood ran a red light and caused a crash that killed one person and sent six others to the hospital.

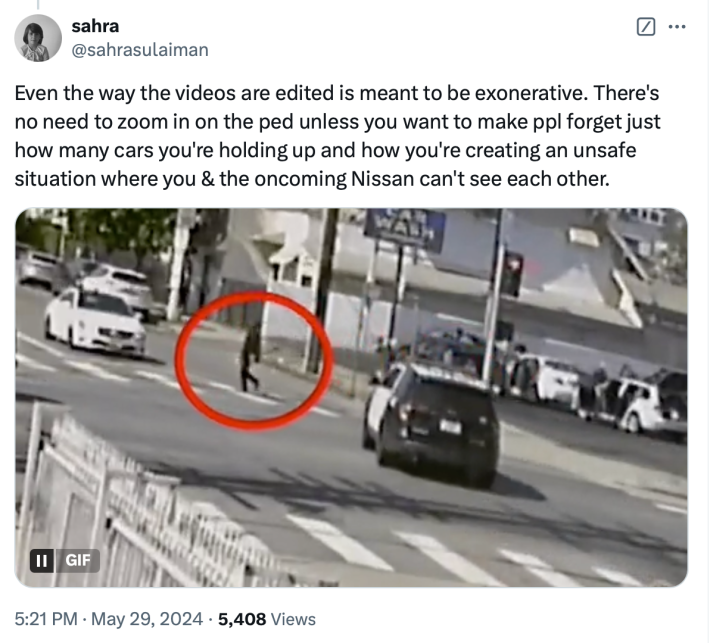

As noted in our deeper dive into pursuits, LAPD's briefing edited the security footage to make it more difficult to see just how recklessly the officers had behaved. And rather than acknowledge how dangerous it was for the officers to have turned off their emergency lights midway across five lanes of traffic, LAPD's briefing opted to shield them - emphasizing that the officers had entered the intersection with their lights flashing.

There seems to be even less accountability around unofficial pursuits like this, where officers break traffic rules in an effort to keep up with a driver or provoke them into committing infractions in order to justify a pretextual stop. Because they generally aren't categorized as pursuits, the pursuit data LAPD produces does not accurately reflect the true picture of how chases are conducted on our city streets.

Take the crash that killed Janisha Harris and Jamarae Keyes at Broadway and Manchester in 2022. Instead of acknowledging officers had been chasing the Cadillac that hit Harris and Keyes when it blew through the red light at Broadway at nearly 70 mph, LAPD denied it was a pursuit. They later walked that claim back, but insisted the pursuit had been extremely brief - lasting about 15 seconds - and that it had been terminated before the fleeing driver ran the red light.

As we reported, that was not exactly true, either. Not only had the chase begun a full minute earlier, LAPD's own footage shows officers aggressively blowing through two red lights prior to flipping on their lights/sirens. And while it is true the officers shut their lights/sirens off two seconds before the Cadillac slammed into Harris and Keyes (below), it appears they may have done so because they were aware they did not have sufficient justification to pursue. To follow the driver as he accelerated to nearly 70 mph, the officers would have had to alert dispatch, formally initiate a pursuit, and account for their decisions. Meaning it is possible they backed off to avoid all that.

The officers certainly were not eager to broadcast their role in the collision. Dispatch was not immediately notified of the crash. And radio chatter captured on a citizen scanner suggests they ascribed it to the driver being under the influence.

Holding LAPD to account for endangering public safety is no small undertaking.

According to the L.A. Times, LAPD spends over $3M a year on two dozen or more people in public relations and communications, which includes the production of briefing videos on deadly incidents like these. In contrast, we just have one person on staff who may spend several days poring over those tax-payer-funded videos and statements in order to piece together a more accurate picture of what really happened.

Safety on our streets is a shared responsibility, as LAPD likes to say. But someone has to make sure they’re also doing their part. We ask that you please help us continue to do that, if you can.

As part of our End of the Year Fundraising Drive, Streetsblog L.A. likes to look back at some of our most influential stories of the year. If you support our work, please consider making a donation today. Get started by clicking here. - DN